Can you diagnose these symptoms? The subject has conceived of a novel innovation that he or she believes is so important it will soon become a staple product across the globe. The inventor thinks its features and benefits solve a problem facing the world. However, our inventor has never queried anyone beyond him or herself and a few friends.

Obviously, no disease or injury was described here, so I think I can handle the diagnosis: inventor’s syndrome.

This condition afflicts numerous creative individuals. It presents itself as a belief that one’s invention has a definite and immediate market, and that sales are just a matter of letting the world know that this new device exists. The good news is that it’s treatable. Here’s the standard of care I recommend.

For any given innovation, there will be a number of user interest or buying parameters—in other words, those elements that affect the customer’s use and buying decision. Let’s think about a new healthcare device for a second. As with any industry, price is a consideration. So is efficacy: does the product reliably do what the user requires? Is it faster? More accurate? Does it save time? Is it less painful and therefore of more interest to patients? Does have to be kept frozen? Is reusable? Do customers prefer it be disposable? If it is reusable, is it easily cleaned? Is it easily ordered and quickly shipped? Does that even matter to the customer? Does the problem allegedly solved by this new product exist at all?

To assess what parameters are important to customers, it’s essential to interface with the market—with all the buyers and users (often two different categories, by the way). In my medical device example, I would include therapists, nurses, physicians, IT folks, engineers or purchasing agents wherever relevant. A survey is a good way to do this, but so is a focus group (more than one is best). And someone more neutral than the inventor needs to be very involved in this process to ensure that survey or focus group participants are not infected with the inventor’s syndrome.

With the buying parameters clarified, the next step is a thorough assessment of all the current solutions to the alleged problem—through the looking glass of those buying parameters. There’s a framework for doing this.

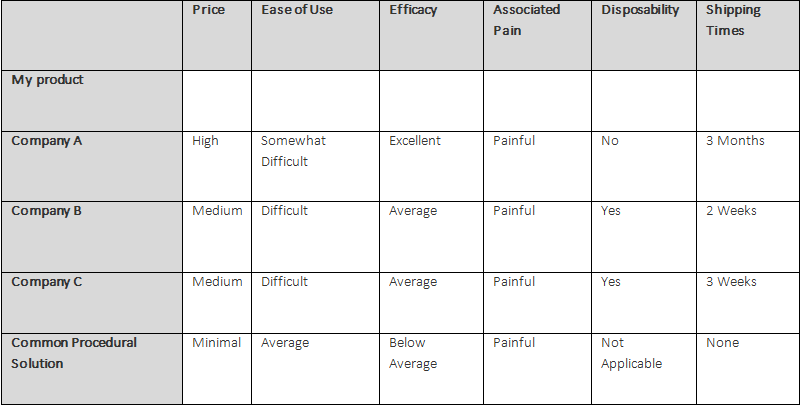

If we have done our work and interfaced with buyers and users, perhaps we now believe we know what is important to them. Let’s say, for example, that we have determined that price, ease of use, efficacy, associated procedure pain, and disposability appear to be the things that are most important to the user, and buyers seem most interested in price and shipping times—plus the assurance that their users want the product.

So how do the competing solutions address these attributes? Notice I said competing “solutions” and not competing products. It is critical to compare your product not just to similar products, but to all the solutions currently being applied by users. It is also important to know what other solutions are in development but not yet in use. Some sleuthing is required. Google searches can be helpful, as many startup companies post simple websites which give hints about their work.

If you put these elements into a table and fill in the information (I completed the table below as a healthcare industry example), you should begin to see how each of the solutions addresses the market needs.

Where does your product fit? Are you able to offer important attributes that others cannot? If not, you need to rethink your product. But, wait, how do you know what your price will be? And what do you know about its efficacy and associated pain. Next I’ll talk about answering these questions.